When on January 18, 1871, after the Franco-German War, the German Empire has been proclaimed and the Prussian King William I is appointed emperor in Versailles, a dream of many Germans comes true – the long-awaited unification of the German lands.

Before this proclamation, the people’s goals towards this Imperial unification strive to achieve that in completely different ways during the German Revolution of 1848 (also named “March-Revolution”). The strict countermeasures of the authorities acting reactionary instead, with no prospect of improvement in people’s living conditions at that point in time. Industrialization progressed inexorably. An assessment from those days regarding the Kingdom of Bavaria states: “At the expense of the center, the right wing had increased significantly in Old Bavaria, but in New Bavaria (!) especially the left party (won), 32 of the 52 electoral districts in FRANCONICA had fallen to them. (…) Even for the liberal politicians in Nuremberg, in which the very moderate Constitutional Association set the tone, despite all the differences in interests and constitutional ideas, the goal was the nation state as a cultural longing, political need and economic hope. It was not uncommon for educated people to express romantic enthusiasm for ‚German‘ (medieval) Nuremberg with its Imperial splendor, as was the case with Hans of Aufsess, the later founder of the Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg[1].

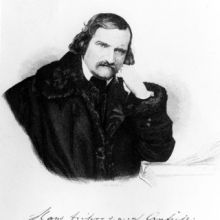

Hans of Aufsess

7/9/1801 – 6/5/1872

Picture of Christoph Riedt

House of Bavarian History, Augsburg

-public domain-

Event sheet from the revolutionary March days 18th/19th March, 1848,

with a barricade scene from Breite Straße, Berlin,

from „Remembrance of the liberation struggle on the fateful night of March 18-19, 1848“,

chalk lithograph, colored,

printed by Winckelmann Publishers,

in possession of C. Glück, Berlin (created between 1848 – 1850)

-public domain-

In Bamberg, the then stronghold of the Democrats, the “Fränkischer Merkur” is published, Upper Franconia’s most influential democratic daily newspaper, which will already been banned in August 1848 for lese majeste and attempted high treason. “The 14 Bamberg Articles” are causing a nationwide sensation because they are not limited to the usual “March demands”, but are formulated in unusually sharp terms, including more civil freedom and political participation, and point to the lower classes with pathos and a social-revolutionary gesture.

The leftist remains a minority in this democratic movement, but agitates with a sense of purpose at many rallies and is the most active with newspaper articles, leaflets and posters[2]. In 1849, the first workers‘ fraternities are formed, starting in Berlin and Leipzig, and also in Franconia – for example in Nuremberg, Fürth, Schwabach, Würzburg, Schweinfurt and Bamberg. The first German workers‘ organizations grow out of them.

As one of the most zealous democrats[3], the carpenter Georg Lochner from Kirchehrenbach (Forchheim district) radicalizes at this time. He is an activist in the revolution of 1848, having stayed briefly in Frankfurt am Main in 1851 and is expelled in January 1852 because he has belonged to both the League of the Righteous and its successor organization, the League of Communists. The latter dissolves in 1852 and is now seen as the nucleus of the world’s later socialist and communist parties and as a forerunner organization of the International Workingmen’s Association (IAA), which has also been inspired by Marx and Engels in 1864 and is now also referred to as the „first international“ of the workers‘ movement[4].

Georg Lochner emigrates to London – like his great role models Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. There he immediately becomes a member of the German Workers’ Educational Association in 1852. The aim of the organization is to educate workers about the machinations of capitalism and thus to awaken the willingness for a revolution by the proletariat. The association is primarily a forum for communist intellectuals[5]. In 1847, the Workers’ Educational Association has around 500 members, and like the communities of the League of the Righteous, they come from all over Europe, in addition to Germans, Scandinavians, Hungarians, Poles, Russians, Italians, Swiss, Belgians, French and English. The international grade is a hallmark of the federal government and the club[6].

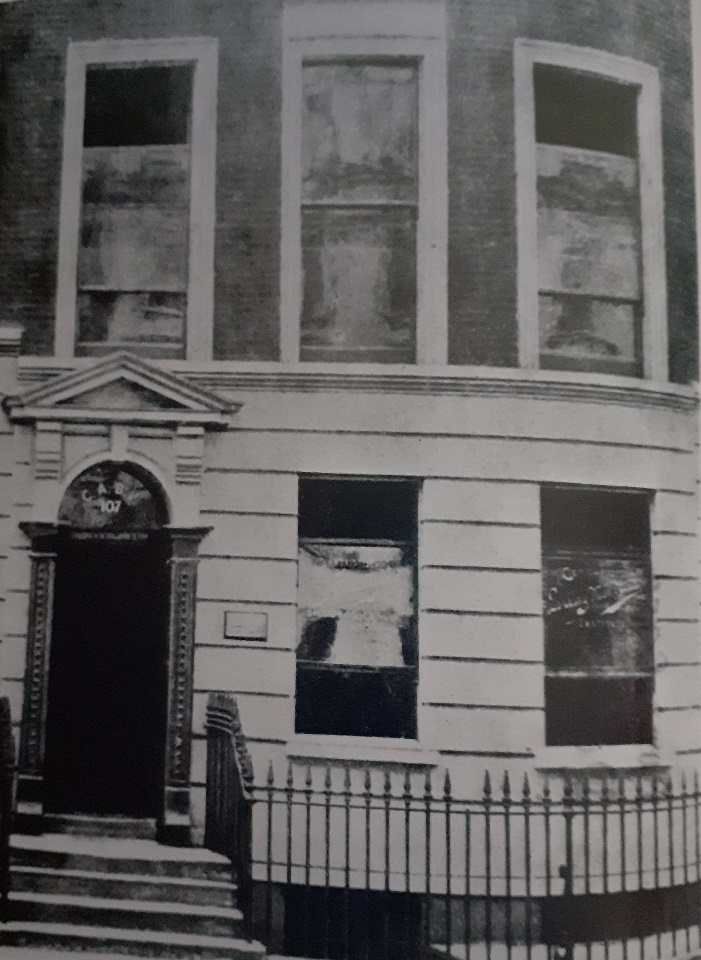

The house of the German Workers’ Educational Association

107, Charlotte Street, London

The house of the German Workers’ Educational Association

107, Charlotte Street, London

above: conference hall

above: bar and library

Photography from: Irma Sinelnikowa: “Frederick Leßner – A biography of the communist

and friend of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels”, Berlin, 1980 –

-with kind permission of Dietz Publishers-

When Frederick Leßner also goes to cosmopolitan London after his imprisonment in the fortress, he joins the German Workers’ Educational Association, resolutely opposing the petty-bourgeois tendencies within the organization. In addition to Georg Lochner, his “old ally” including Carl Pfänder – Marx follows the ideological debate with great interest. He agreed to publish the German Workers’ Educational Association’s own newspaper called „Das Volk“, which appears for a short time in May 1859. To clarify editorial questions, Marx invites his closest confidants: William Liebknecht, Frederick Leßner, Carl Heinrich Pfänder and Georg Lochner[7].

Now, time has come: in London’s St. Martin’s Hall, during the founding conference from September 25th to 29th, 1864, the International Workingmen’s Association, abbreviated IAA, is founded on September 28th, 1864[8]. At the suggestion of Marx himself, Georg Lochner is appointed to the General Council of the 1st International – like his old friends Leßner and Pfänder[9]. He remains there in the years 1864 – 1867 and 1871/1872. It can therefore justifiably be claimed that Lochner is a personality of the German and International Workers‘ Movement[10].

On March 14, 1883, Karl Marx dies: In 1848, together with Frederick Engels, he publishes the 23-page Communist Manifesto – a programmatic text in which large parts of the worldview later known as „Marxism“ are written down, with an introduction and it consists of four chapters, saying “Proletarians of all countries, unite!”[11]

His main work, “Capital – Critique of Political Economy”, is an analysis and criticism of capitalist society with far-reaching effects in the labor movement and the history of the 20th century. Marx’s personal edition of „Capital – 1st Volume“ from 1867 (MEW Volume 23) – with his handwritten annotations – will be included in the World Register of Documentary Heritage by UNESCO in June 2013 at the joint proposal of the Netherlands and Germany. After Marx’s death, Frederick Engels will compile two further volumes from his manuscripts.

In 1885 he publishes Volume 2: “The Circulation Process of Capital” (MEW Volume 24), which in 1894 Volume 3: “The Overall Process of Capitalist Production” (MEW Volume 25) will follow[12]. Leßner and Lochner congratulate Frederick Engels profusely in a joint letter dated November 28, 1894[13].

In his letter of June 15, 1891 to Frederick Engels, Georg Lochner writes literally: “In the past – when Marx was still alive – on my long way to work, I usually looked back on past times; I was always worried that we would lose this man, if he died too early. That’s how I feel about you now”[14]. And in his letter of April 16, 1883, immediately after the death of Karl Marx, there is a similar formulation about Frederick Engels: “Because of the death of Marx, which is never enough to be lamented, your shoulders will have to bear new and difficult work, (…) and you will have to continue and supplement Marx’s work. I remember that when we talked about the possible interruption of his work, Marx expressed himself in the same spirit”[15]. This clearly shows what a close friendship Georg Lochner has with Karl Marx and Frederick Engels!

Marx himself writes in a letter to Louis Kugelmann to Hanover on December 12, 1868: “…a third workman who could give lectures on my book, is Lochner, a carpenter, who has been here in London about fifteen years”[16].

In the three handwritten letters from Georg Lochner to Frederick Engels (see: 03 CORRESPONDENCE Georg Lochner) his personality shines through, including the fact that he is a well-read man and is genuinely happy when Engels sends him a brochure, for example about “Prussian schnapps” and complains, “…it would be good for us to be acquainted with original, free and ruthless views that differs from the mass of rubbish that one has to read through in order to follow the events of the day to some extent”[17]. The living conditions and earning potential in London at that time are miserable[18]. His friend Carl Heinrich Pfander dies of tuberculosis in 1876. Lochner must have been married; as a carpenter, he lives with at least one son named George junior (wife Madaleine, maiden name unknown). His address 5 Sussex Place, Bridge Road, Hammersmith, London is in the Western part of the British capital, on the north bank of the Thames. His commute seems to have been quite long (see above).

In 1855, death takes Marx’s little son named Edgar – both parents are heartbroken about the death of their little Musch. The old faithful gather again at the grave, including Georg Lochner[19]. This is reported by Edward Aveling, the partner of Marx’s daughter Eleanor, and further confesses that around 1890 “…of those Germans who still live in London, veterans of the International, such as Frederick Leßner (…), and (William ) Liebknecht (…) is the gentle, modest, yet energetic Lochner (one of the oldest friends of Marx and Engels), the only survivor of the old communist alliance…“[20].

Edgar –Musch– Marx

3.2.1847 – 6.4.1855

son of Karl and Jenny Marx

Contemporary drawing on cardboard,

bromine silver print around 1850 –

German Historical Museum, Berlin

-public domain-

The German journalist and politician Franz Mehring gives a similar assessment in the “Leipziger Volkszeitung” on the 80th birthday of Frederick Leßner on February 27, 1905): “…Leßner is not the only veteran from the Communist League era who is still alive today. Together with him, through loyal friendship and the brotherhood in arms of almost six decades, Georg Lochner still lives in London today, even a few years older than Leßner, a comrade in arms from the time of the Communist League and the International. (…) Lochner moved from Germany to England shortly before the communist agitation broke out in Germany, not to keep himself safe, but because in the days of reaction the propaganda seemed as hopeless to him as it did to his Nuremberg comrades”[21].

When Frederick Engels dies on August 5, 1895, a grief-stricken Georg Lochner followed the coffin. Perhaps he will also have buried his old friend Leßner on February 1, 1910 – he himself seems to have passed away between 1905 and 1910. So, he no longer has to experience the bitterness of the events of the First World War, in which his grandson George Cecil Lochner died on July 2, 1916, when reaching French soil, and that at the age of 28. He lies in the military cemetery of Ecoivres, Mont-Saint-Elois (II.E.28)[22]. Research into today’s descendants of the loyal friend of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels has so far come to nothing[23].

In Memory Of Rifleman

GEORGE CECIL LOCHNER

Service Number: 2890

2nd/18th Bn., London Regiment (London Irish Rifles) who died on 02 July 1916 Age 28

Son of George and Madaleine Lochner of London.

Remembered with Honour

ECOIVRES MILITARY CEMETERY, MONT-ST. ELOI

II. E. 28.

- Werner K. Blessing: „1848/49 – Revolution in Franconia“, House of Bavarian History and Culture, Volume 22, Augsburg, 1999 – p. 20 ↑

- Werner K. Blessing: „1848/49 – Revolution in Franconia“, House of Bavarian History and Culture, Volume 22, Augsburg, 1999 – pp. 24/25 ↑

- Carl G. Wermuth/Wilhelm Stieber: „The communist conspiracies of the 19th century“, Berlin, 1854 – p. 75 ↑

- Martin Hundt (Hrsg.): „League of Communists 1836–1852“, Akademie Publishers, Berlin, 1988 ↑

- “German Workers’ Educational Association“, in: „Encyclopedia of the history of Germany and the German workers‘ movement“, Volume 2, Dietz Publishers, Berlin, 1970,p.44 ↑

- Irma Sinelnikowa: “Frederick Leßner – A biography of the communist and friend of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels”, Dietz Publishers, Berlin, 1980 – p. 23 ↑

- Irma Sinelnikowa: “Frederick Leßner – A biography of the communist and friend of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels”, Dietz Publishers, Berlin, 1980 – p. 92 ↑

- Karl Marx: “Provisional Statutes of the International Workingmen’s Association“ – in: Marx-Engels-Works, Volume 16, p. 15 ↑

- Hans Müller: “A forgotten Revolutionist from Heilbronn: Carl Heinrich Pfänder (1819 – 1876)“, heilbronnica 4 – Editors: C. Schrenk, P. Wanner, Contributions to city and regional history; sources and research on the history of the city of Heilbronn 19; Yearbook for Swabian-Franconian History 36, Heilbronn City Archives, 2008 – p. 300 ↑

-

Franz Mehring: “Karl Marx – History of his life“, Collected writings, Volume 3, Berlin/GDR, 1960 – pp. 256/330↑

- Iring Fetscher, Publisher of the Marx-Engels study edition, assumes in his foreword that the text was created by Karl Marx alone – Engels provided preparatory work for it (Fischer pocket book no. 6061, p. 9). Fetscher’s view is not shared by the more recent editors (e.g. Wolfgang Meiser or Thomas Kuczynski) ↑

- MEW = Marx-Engels-Works, Dietz Publishers, Berlin, 1962 – 1964 ↑

- Regina Roth, Eike Kopf, Carl-Erich Vollgraf (Editors): “Karl Marx – Capital“, Akademie Publishers, Berlin, 2004 ↑

- Letter from Georg Lochner to Frederick Engels: International Institute of Social History – Amsterdam – Netherlands – Letter No. 3 of 1891 = L_3615 ↑

- Letter from Georg Lochner to Frederick Engels: International Institute of Social History – Amsterdam – Netherlands – Letter No. 2 of 1883 = L_3614 ↑

- https://www.marxists.org / Marx-Engels-Collected-Works, Volume 43, p. 184, first publication in “Die Neue Zeit“, Stuttgart, 1901 – 1902 – International Institute of Social History – Amsterdam – Netherlands, Marx-Engels-Residue, C 357/C 116 ↑

- Letter from Georg Lochner to Frederick Engels: International Institute of Social History – Amsterdam – Netherlands – Letter No. 3 of 1876 = L_3613 ↑

-

Franz Mehring: “Karl Marx – History of his life“, Collected writings, Volume 3, Berlin/GDR, 1960 – pp. 256/330↑

- Marxists Internet Archives, London, U.K.: “Reminiscences of Marx and Engels”, p. 115 ↑

- Marxists Internet Archives, London, U.K.: “Reminiscences of Marx and Engels”, Kapitel Edward Aveling, Dr. Sc. Engels at home – p. 312 ↑

- Leipziger Volkszeitung (Leipzig’s newspaper for people) of 27th February 1905 – new print in Franz Mehring: “Collected writings“, Volume 4, Berlin, 1960 – 1967, pp. 442 – 444 ↑

- https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/65657/george-cecil-lochner – see next page… ↑

- Just to the contrary, Mr. Hans Müller found out of Carl Heinrich Pfänder, and describes that in an essay: „A forgotten Revolutionist from Heilbronn: “Carl Heinrich Pfänder (1819 – 1876)“, heilbronnica 4 – Editors: C. Schrenk, P. Wanner, Contributions to city and regional history; sources and research on the history of the city of Heilbronn 19; Yearbook for Swabian-Franconian History 36, Heilbronn City Archives, 2008 – p. 315:

Victoria Caroline Adams, world-famous as a former member of the pop group Spice Girls and married to English football star David Beckham, is a direct descendant of Carl Heinrich Pfänder – afterwards the family changed their name into “Pfander” ↑